The Federal Reserve Board’s academic approach to managing the economy has been flunking out.

Some are making the argument that the Federal Reserve Board could use a fresh perspective – one less rooted in academia and more in the real world. As we’ve previously noted, the Fed has been described as “a tribe of slow-moving … economists who dismiss those without high-level academic credentials.”

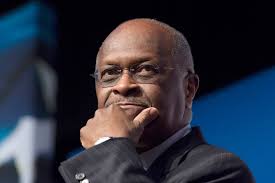

There are plenty of examples of how the “professor standard,” as Herman Cain calls it, has led to illogical and potentially harmful decisions by the Fed.

Cain, the former presidential candidate who was being considered to serve on the Federal Reserve Board by President Trump, withdrew his name because of accusations of sexual harassment. But his point about appointing only academicians to the Fed is well taken. Consider some of the consequences:

- The Fed still relies on the Phillips curve, which predicts an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation, in its decision making. The real world abandoned it during the 1973-1975 recession, when unemployment and inflation were both high. Today, we have low inflation combined with one of the lowest rates of unemployment ever recorded.

- Fed growth forecasts are almost always wrong. Throughout the Obama administration, the Fed regularly overestimated growth in its forecasts. Throughout the Trump administration, the Fed has regularly underestimated growth.

- The Fed set a 2% inflation rate as a seemingly arbitrary goal and used the need to reach this goal as a reason for continuing its zero interest rate policy (ZIRP). In 1979, when inflation spiked out of control during the Carter Administration, Congress mandated that the Fed bring the rate of inflation to zero within a decade. It never achieved that goal and it’s never been clear why that goal was abandoned.

- The Fed regularly uses language that no one understands. “Bond buying” becomes “quantitative easing,” and when you reduce it, you’re “tapering.” Information about the Fed’s future action is “forward guidance.” The Fed also flirted with “macroprudential supervision,” but abandoned the idea because apparently even the Fed didn’t know what macroprudential supervision means.

- Potentially most damaging was the Fed’s decision to purchase trillions of dollars’ worth of bonds, boosting its portfolio from less than $1 trillion to $4.5 trillion. The Fed recently ceased its efforts to “normalize” its portfolio, because doing so was spooking the markets.

According to Cain, the Phillips curve, “the favorite tool” of academicians, “tells them wage growth that is too strong can cause an outbreak of 1970s-style inflation.”

With wages rising at a rate of more than 3% a year, while inflation has been below 2% for four consecutive months, Cain argued in a Wall Street Journal commentary that the Fed should abandon the Phillips curve and instead focus on stabilizing the dollar.

“Since the Federal Reserve Act of 1913, there have been three distinct periods of sustained dollar stability: 1922-29, 1947-70 and 1983-99,” according to Cain. “During these periods, real growth of gross domestic product averaged 3.9% a year and real income growth for the bottom 90% averaged 2.2%.”

During periods of dollar volatility, he added, real GDP growth averaged only 1.9% and real income for the bottom 90% declined by an average of 1.3% annually.