The world is slowing down.

No country escapes a recession forever, whether your country is capitalist or socialist or something in between.

Communist and fascist countries are generally in a permanent downward cycle, with citizens suffering from different degrees of misery. China, which has enjoyed rapid economic growth in recent years, has been an exception, but much of its success is due to the size of its market and its habit of stealing other countries’ intellectual property.

Before the Internet, countries were less codependent on each other than they are today. Before globalization, the Internet and other changes that have made the world a smaller place, one country’s recession often had little impact on another country’s economic boom.

Today, though, a recession in one part of the world can lead to a recession elsewhere. In announcing the Fed’s decision to stop raising interest rates, Chair Jerome Powell cited cooling growth in Europe and Asia, as well as trade disputes and Brexit.

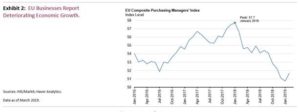

Today, all of Europe seems to be sharing an economic slowdown — in spite of, or maybe to some extent because of, the European Union.

The EU’s Purchasing Managers’ Index (PMI) hit a high of 57.7 in January 2018, but economic growth has slowed because of a stronger euro, rising oil prices and constraints on industrial capacity, according to Joe Quinlan, who heads CIO Market Strategy for Merrill and Bank of America Private Bank. He added that the U.S. steel and aluminum tariffs that began in March 2018 “battered business confidence in Europe and disrupted transatlantic trade volumes.”

Manufacturing, which has been keeping the Eurozone out of a recession, recently entered its first downturn since mid-2013. According to The Wall Street Journal, “Overall economic activity in the bloc slowed more sharply than expected last year and seems set to cool further this year, undermined by trade frictions, uncertainty about the severity of China’s own slowdown and a potentially messy U.K. departure from the European Union.”

When growth slows in Europe, it has a significant impact on the U.S. economy, because American companies earn considerable profits from their European operations. Data released recently from the Bureau of Economic Analysis show that U.S. corporate earnings from European operations increased 7% in 2018 to a record $284 billion. That’s about triple the profits produced from all of Latin America or all of Asia.

Quinlan also noted that “of the 200 economies that make up the global economy, the ‘Big Three’ – United States, China and Europe – account for 60% of world GDP and global consumption, and 55% of world trade and cross-border investment.”

Loose Monetary Policy Didn’t Work

The U.S. economy, though slowing, is still in better shape than any other major economy. And, because the Federal Reserve Board has raised interest rates nine times since its zero interest rate policy (ZIRP) ended, there’s room to move in the opposite direction and lower rates.

Not so in Europe, which adopted negative interest rates and just ended its quantitative easing program in January. While the European Union is not in a recession, its economy have been growing at a relatively slow rate. The European Commission recently sharply downgraded its forecast for Eurozone economic growth, predicting a growth rate of just 1.3% this year, down from 1.9% for 2018, with a modest rebound to 1.6% in 2020.

Many European countries have also been plagued by problems that are a drag on their economies. The United Kingdom’s inability to reach an agreement over how to implement Brexit and widespread protests in France over a tax to pay for policies to help prevent climate change are two prominent examples.

Meanwhile, the U.S. has been slowly increasing interest rates for two years and the economy has been growing at a rate of more than 3% a year.

How much good did Europe’s negative interest rates do? They may have helped the U.S. most, because here, with interest rates near zero, yields were more attractive (or less ugly) than those in Europe.

If another recession is coming, as it appears to be, what will the European Central Bank do? If the ECB needs to lower rates to boost economic growth, will it drop its negative rates even lower? Will the ECB just give money away and encourage Europeans to spend it?

In a best case scenario, countries throughout Europe would follow the American example by deregulating and reducing interest rates. They may have little other choice. After all, they’ve just proved, once again, that Keynesian economics doesn’t work.