Part three of a three-part series.

When a company goes public through an initial public offering (IPO), it raises capital for expansion by issuing new shares of its stock. While the potential for future growth can boost the value of the stock, the increase in the number of shares may dilute the stock’s value.

It’s like slicing a pie into more pieces. The size of the pie remains the same, but more pieces results in each piece being smaller.

Some companies go public through a direct listing, in which existing stock becomes available for public trading. Because companies that use a direct listing do not issue more shares, there is no dilution and companies save on the cost of underwriting, which can be significant for a small company.

Investors should especially be wary of dilution when they consider investing in a special-purpose acquisition company, or SPAC.

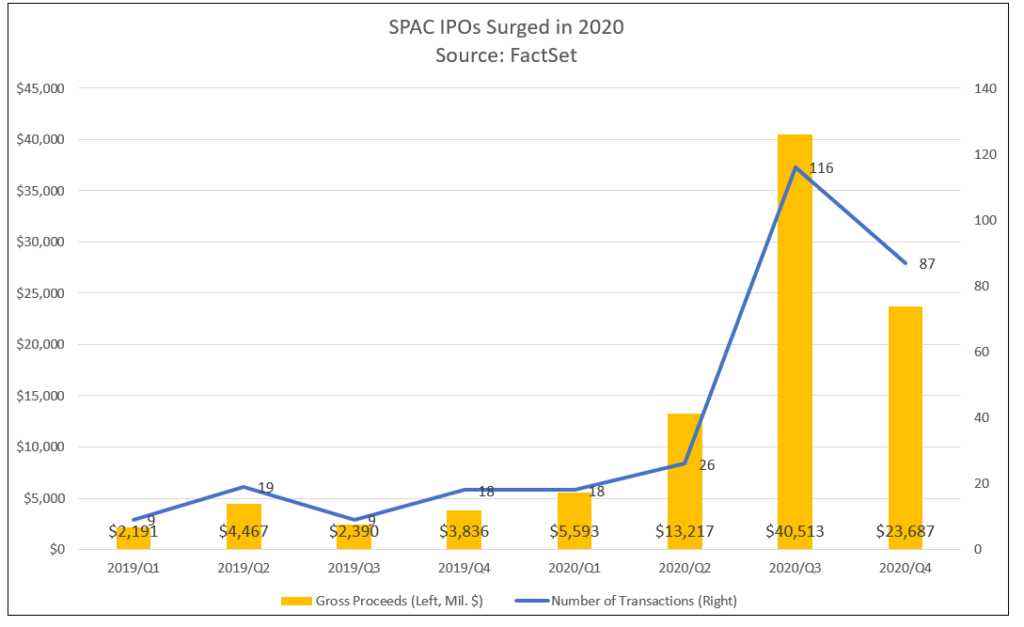

The Wall Street Journal reported that nearly half of all fundraising in the IPO market in 2020 was for SPACs. SPACs raised more equity in 2020 than over the entire preceding decade, according to Stanford Law School Professor Michael Klausner and management consultant Emily Ruan.

But SPACs are called blank-check companies for a reason. A SPAC is a shell company that a “sponsor” organizes and takes public. The SPAC holds cash and has two years to find a private company with which to merge and then go public. The sponsor, which may be a group or an individual, invests capital in return for equity, but takes an additional 20% interest in the SPAC at a nominal price.

The sponsor seeks investments in units containing one share, plus a “right,” a warrant or both. Investors — often hedge funds — can purchase units for $10 each, but if they decide not to participate in the merger, they can redeem their shares for $10 plus interest, and keep the warrants and rights.

“This is a tremendous deal for IPO investors who redeem their shares,” Klausner and Ruan wrote in The Wall Street Journal. “A right gives a unit holder an additional one-tenth of a SPAC share when the merger is complete. A typical warrant gives the holder an option to buy between one-half and one share at an exercise price of $11.50 any time over five years following the SPAC’s merger. On average, if an investor buys units in a SPAC public offering, redeems its shares and keeps or sells its warrants and rights, the investor’s annualized return is more than 10% with no downside risk.”

Sponsors often do even better. For the period January 2019 to June 2020, sponsors enjoyed a return averaging more than 500% as of the end of 2020. Investors who invested in the post-merger public company, though, lost an average of 12% in the six months after the merger, even as the Nasdaq index rose about 30%.

“It is not a coincidence that sponsors and SPAC IPO investors who redeem their shares earn a high return, while shareholders who remain invested through the merger do poorly,” according to Klausner and Ruan. “The sponsors’ essentially free shares and the IPO investors’ free warrants and rights dilute the returns to investors. The shareholders who pay for their investments are, in effect, sharing the value of the merged company with others who did not.”

In other words, SPACs are popular because they create a great deal of wealth — for sponsors and the hedge funds that are pre-merger investors. The average investor, conversely, is subsidizing their gains while bearing the risk.

In spite of the downside of SPACs and the limited access average investors have to IPO stocks, the resurgence of IPOs is good news, as it will fuel the growth of the next generation of companies that will create jobs, spur economic growth and give the stock market a boost.